One-Way Randomized Blocks Design & Introduction to Two-Way ANOVA

STAT 218 - Week 10, Lecture 1

March 11th, 2024

Introduction

In a randomized blocks design,

- We first group the experimental units into sets, or blocks, of relatively similar units

- We randomly allocate treatments within each block.

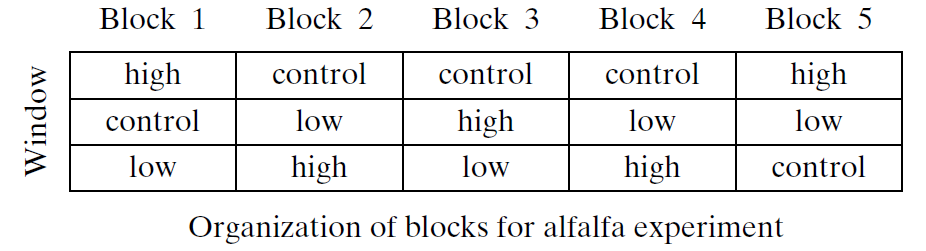

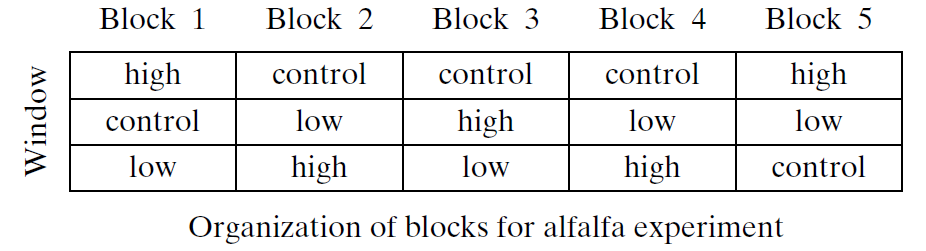

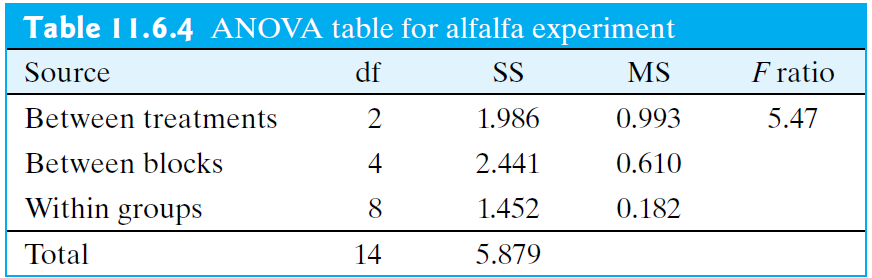

Example: Alfalfa and Acid Rain Researchers were interested in the effect that acid has on the growth rate of alfalfa plants.

- They created three treatment groups (IV) in an experiment: low acid, high acid, and control.

- The response variable (DV) in their experiment was the height of the alfalfa plants in a Styrofoam cup after 5 days of growth.

- They had 5 cups for each of the 3 treatments, for a total of 15 observations.

- However, the cups were arranged near a window and they wanted to account for the effect of differing amounts of sunlight.

- Thus, they created 5 blocks —each block was a fixed distance away from the window (block 1 being the closest through block 5, the farthest).

- However, the cups were arranged near a window and they wanted to account for the effect of differing amounts of sunlight.

- Within each block the three treatments were randomly assigned.

But Why?

In general, we create blocks

- in order to reduce or eliminate variability caused by extraneous variables

- so that the precision of the experiment is increased.

- We want the experimental units within a block to be homogeneous;

- We want the extraneous variability to occur between the blocks.

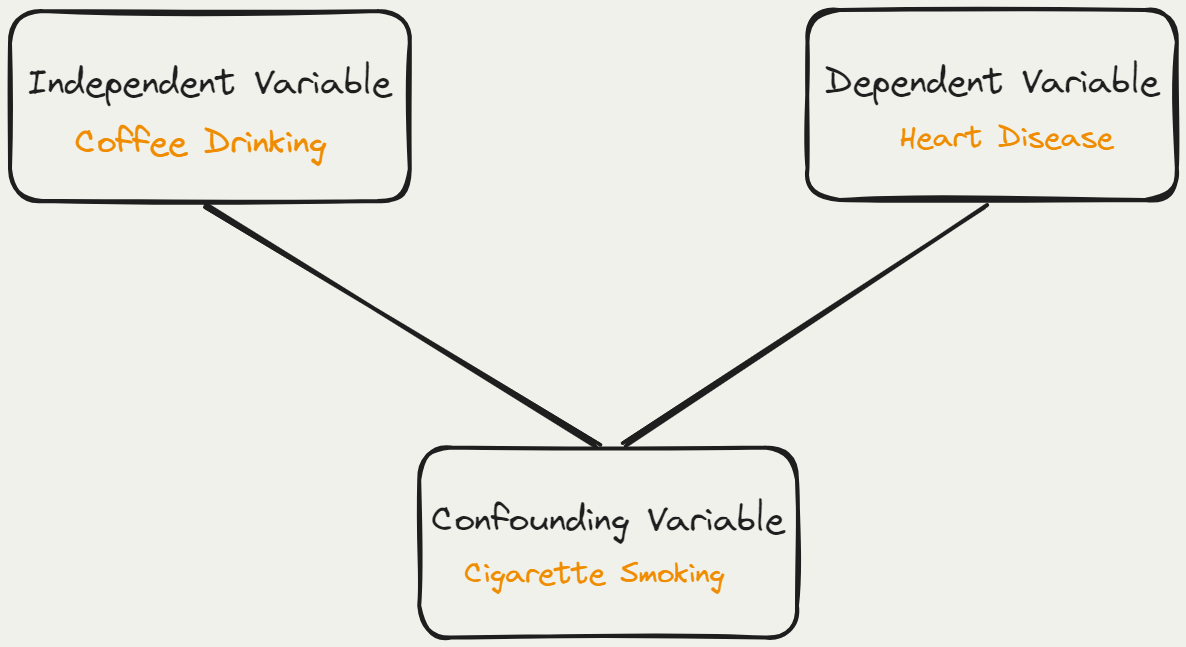

Confounding Variable vs Extraneous Variable

- If an extraneous variable is not appropriately controlled, it may be unequally present in the comparison groups. As a result, the variable becomes a confounding variable.

- In other words, all confounding variables are extraneous, but not all extraneous variables are confounds.

- A confounding variable (confounder) is a factor other than the one being studied that is associated both with the disease (dependent variable) and with the factor being studied (independent variable).

Confounding Variable vs Extraneous Variable

Creating the Blocks

Creating the Blocks

As the preceding examples show, blocking is a way of organizing the inherent variation that exists among experimental units.

Ideally, the blocking should be arranged so as to increase the information available from the experiment.

- To achieve this goal, the experimenter should try to create blocks that are as homogeneous within themselves as possible so that the inherent variation between experimental units becomes, as far as possible, variation between blocks rather than within blocks

Another Example for Blocking

Blocking in an Agricultural Field Study

When comparing several varieties of grain, an agronomist will generally plant many field plots of each variety and measure the yield of each plot.

Differences in yields may reflect not only genuine differences among the varieties, but also differences among the plots in soil fertility, pH, water-holding capacity, and so on.

- Consequently, the spatial arrangement of the plots in the field is important.

An efficient way to use the available field area is

- to divide the field into large regions—the blocks—and

- to subdivide each block into several plots.

- Within each block the various varieties of grain are then randomly allocated to the plots, with a separate randomization done for each block.

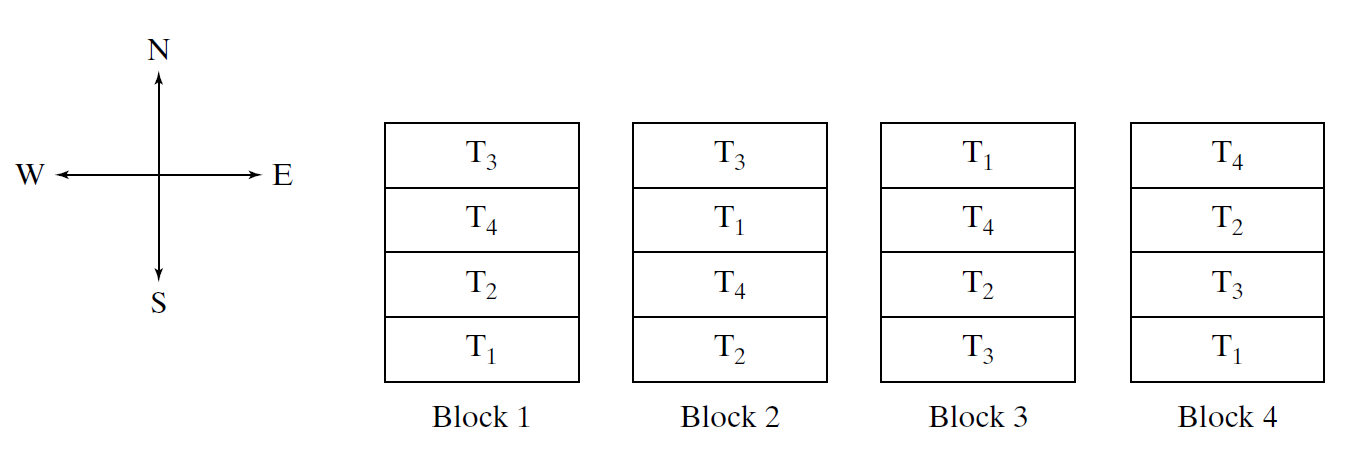

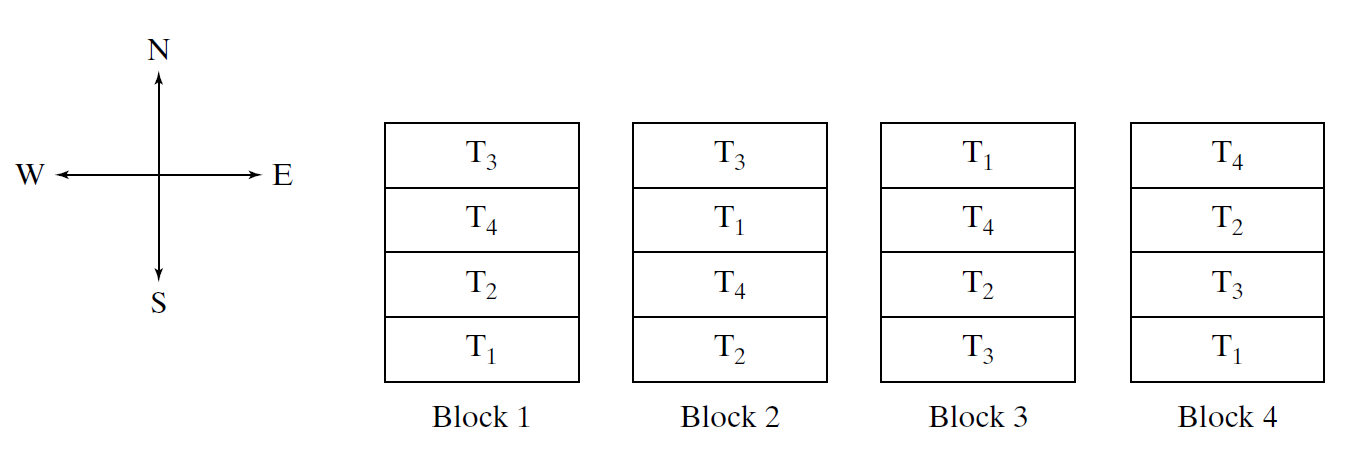

- For instance, suppose we want to test four varieties of barley.

- Then each block would contain four plots.

- The resulting randomized allocation might look like Figure 11.6.2, which is a schematic map of the field.

- The “treatments” \(T_1\), \(T_2\), \(T_3\), and \(T_4\) are the four varieties of barley.

- For instance, suppose we want to test four varieties of barley.

Agricultural Field Study (cont.d)

For the barley experiment of Example 11.6.4, how would agronomists determine the best arrangement or layout of blocks in a field? (Discuss with your neighbor)

- They would design the blocks to take advantage of any prior knowledge they may have of fertility patterns in the field.

- For instance, if they know that an east–west fertility gradient exists in the field (perhaps the field slopes from east to west, with the result that the west end has a thicker layer of good soil or receives better irrigation),

- then they might choose blocks as in Figure 11.6.2;

- For instance, if they know that an east–west fertility gradient exists in the field (perhaps the field slopes from east to west, with the result that the west end has a thicker layer of good soil or receives better irrigation),

- The layout maximizes soil differences between the blocks and minimizes differences between plots within each block.

- (But even if a field appears to be uniform, blocking is usually used in agronomic experiments, because plots closer together in the field are generally more similar than plots farther apart.)

The Randomization Procedure

Once the blocks have been created, the blocked allocation of experimental units is straightforward:

- It is as if a mini-experiment is conducted within each block.

- Randomization is carried out for each block separately,

Agricultural Field Study (cont.d)

Consider the agricultural field experiment of Example 11.6.4.

- In block 1, let us label the plots 1, 2, 3, 4, from north to south (see Figure 11.6.2); we will allocate one plot to each variety.

- The allocation proceeds as for the completely randomized design, by choosing plots at random from the four, and assigning the first plot chosen to \(T_1\), the second to \(T_2\), and so on.

- For instance, using a computer to randomly permute the numbers 1 through 4 (or even shuffled cards numbered 1 through 4) we might obtain the sequence 4, 3, 1, 2, which would lead to the following treatment allocation.

| Block 1 | |

|---|---|

| T1 | Plot 4 |

| T2 | Plot 3 |

| T3 | Plot 1 |

| T4 | Plot 2 |

- This is in fact the assignment shown in Figure 11.6.2 for block 1. We can then repeat this procedure for blocks 2, 3, and so on.

Analyzing Data from a Randomized Block Experiment

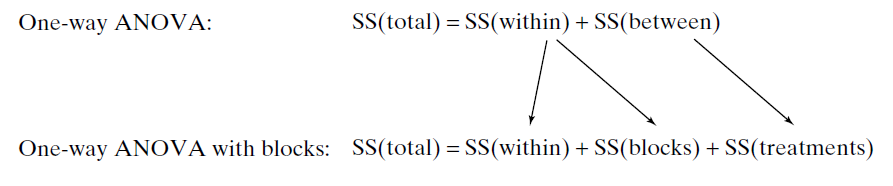

In the same way we cannot use a two-sample t test when data are paired, when an experiment has been blocked, we no longer can use our ANOVA methods that we learned in Section 11.4.

- Instead, we will use a randomized blocks ANOVA model.(You are not responsible to calculate \(F\) statistic for this)

Analyzing Data from a Randomized Block Experiment

Two Way ANOVA

What is Two Way ANOVA?

Factorial ANOVA

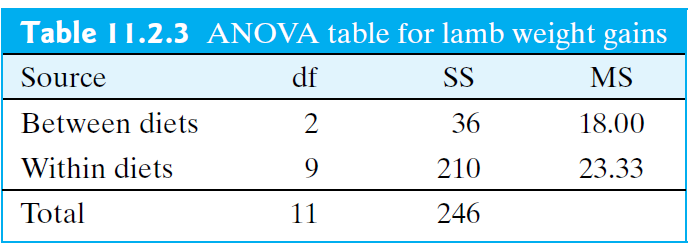

In a typical analysis of variance application there is a single explanatory (independent) variable or factor under study.

- For example, in the previous lecture, we compared weight gain of lambs for the three types of diet: diet 1, diet 2, and diet 3.

- Let’s assume that we found a significant difference between diet 1 and diet 3.

- We may wonder if this is the case for both males and females?

- One-way ANOVA cannot answer this question.

- We may wonder if this is the case for both males and females?

- Let’s assume that we found a significant difference between diet 1 and diet 3.

When do we need to use this test?

Two-way analysis of variance allows you to test the impact of two independent variables on one dependent variable.

The advantage of using a two-way ANOVA is that it allows you to test for an interaction effect

- that is, when the effect of one independent variable is influenced by another;

Interaction Effect

The concept of interaction occurs throughout biology.

- The terms “synergism” and “antagonism” describe interactions between biological agents.

- The term “epistasis”describes interaction between genes at two loci.

- When interactions are present, the main effects of factors don’t have their usual interpretations.

- Because of this, we usually test for the presence of interactions first.

- If interactions are present, then we often stop the analysis at this stage and focus on the interaction effect.

- If no evidence for an interaction effect is found (i.e., if we do not reject \(H_0\)), then we proceed to testing the main effects of the individual factors.

- Because of this, we usually test for the presence of interactions first.

- When interactions are present, the main effects of factors don’t have their usual interpretations.

An Example

Growth of Soybeans A plant physiologist investigated the effect of mechanical stress on the growth of soybean plants. Individually potted seedlings were randomly allocated to four treatment groups of 13 seedlings each. Seedlings in two groups were stressed by shaking for 20 minutes twice daily, while two control groups were not stressed. Thus, the first factor in the experiment was presence or absence of stress, with two levels: control or stress. Also, plants were grown in either low or moderate light. Thus, the second factor was amount of light, with two levels: low light or moderate light. This experiment is an example of a 2 * 2 factorial experiment; it includes four treatments:

Treatment 1: Control, low light

Treatment 2: Stress, low light

Treatment 3: Control, moderate light

Treatment 4: Stress, moderate light

After 16 days of growth, the plants were harvested, and the total leaf area (\(cm^2\)) of each plant was measured.

Categorical IVs: (1) Presence or absence of stress and (2) Amount of light with 2 levels

Continuous DV: total leaf area (\(cm^2\))